Many people in northeastern Washington and north Idaho were treated to the celestial experience of the Aurora borealis beginning on May 10, and for several nights after. The Aurora borealis was named as such by Galileo in 1619 and is a combination of the words “Aurora” from the Roman Aurora, the goddess of the dawn, and the Greek name for the north wind Boreas. This natural light show is also called the “northern lights.”

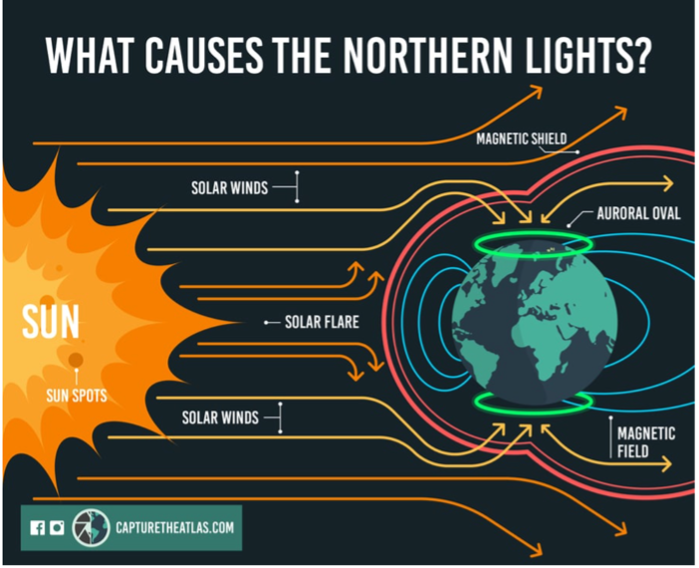

The phenomenon is a result of the earth’s geomagnetic field interacting with solar winds released by the sun. According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the geomagnetic field of the earth is due to the composition of the earth’s inner and outer core; iron and nickel. The inner core is a solid mass and about as hot as the sun. The heat of the core causes the more fluid, outer core to heat and cool, creating convection cells. This rise and fall of iron and nickel create something similar to the straight bar magnets many people played with in elementary school. This magnet runs along the axis of the earth, with particles being absorbed and released from the northern and southern poles respectively. This magnetic field is called the magnetosphere. The magnetosphere normally interacts with particles released from the sun that are hurling towards the planet at over one million miles per hour in a fairly benign manner. These interactions go largely unnoticed, and any light shows that accompany them are relegated to the north and south poles in an area called the auroral zone.

However, when the sun gives of burst of extremely high levels of charged particles in a solar wind, the magnetosphere becomes overloaded by particles. In these high intensity solar winds, there are simply too many particles coming at the magnetosphere at once. This causes the auroral zone to shift to lower latitudes. The immense number of charged particles of the solar wind also begin to interact with the atoms in the atmosphere instead of being absorbed by the magnetosphere. The atoms these charged particles most commonly interact with are oxygen and nitrogen.

There are four main colors to the Aurora borealis and all of them were seen over northeastern Washington. According to Maia Mulko of Interesting Engineering, the colors give an indication to the intensity of the solar winds. The color red is produced by the solar particles exciting oxygen molecules high in the atmosphere (above 150 miles from the earth’s surface). Since there are very few particles of oxygen there, it takes an immense amount of solar wind particles collide with the oxygen. Green is another color given off by oxygen, but is usually closer to the earth’s surface, as this is where there is a greater concentration of oxygen atoms. Purples and blues are a result of the interaction between the charged particles and nitrogen, with purples being viewed when the interactions are occurring 60 miles above the surface of earth and blues being viewed when the particles break through to within 60 miles of the earth’s surface.

There are many legends surrounding the Aurora borealis. Forbes Magazine senior contributor David Nikel explored such legends in his article, “Myths And Legends About The Northern Lights.” According to Nikel, some Native American stories depict the northern lights as torches held by ancestors leading the souls of the recently deceased as they crossed over into the lands beyond. To communicate with people on Earth, they believed the northern lights made a whistling sound, which was to be answered by humans with whispers. This last part can be attributed to the fact the Aurora borealis truly does make a whistling noise at times, as discovered by professor Unto K. Laine of Aalto University in Finland in 2012, but researchers are still not exactly sure how.

Nikels goes on to describe how the Vikings believed the Aurora borealis were simply the reflections of the Valkyries’ shiny armor as they led the warriors to Odin. Other Nordic legends claim the Aurora borealis was the breath of brave soldiers who died in combat.

As rare as the Aurora borealis is, its appearance is at least becoming somewhat more predictable. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provides information on the likelihood of upcoming light displays at https://www.noaa.gov.

Gretchen Cruden has long loved nature, science, and teaching others about the world around them. No wonder she teaches an entire middle school at the Orient School and, in her free time, often finds herself outside, playing in nature with her family.